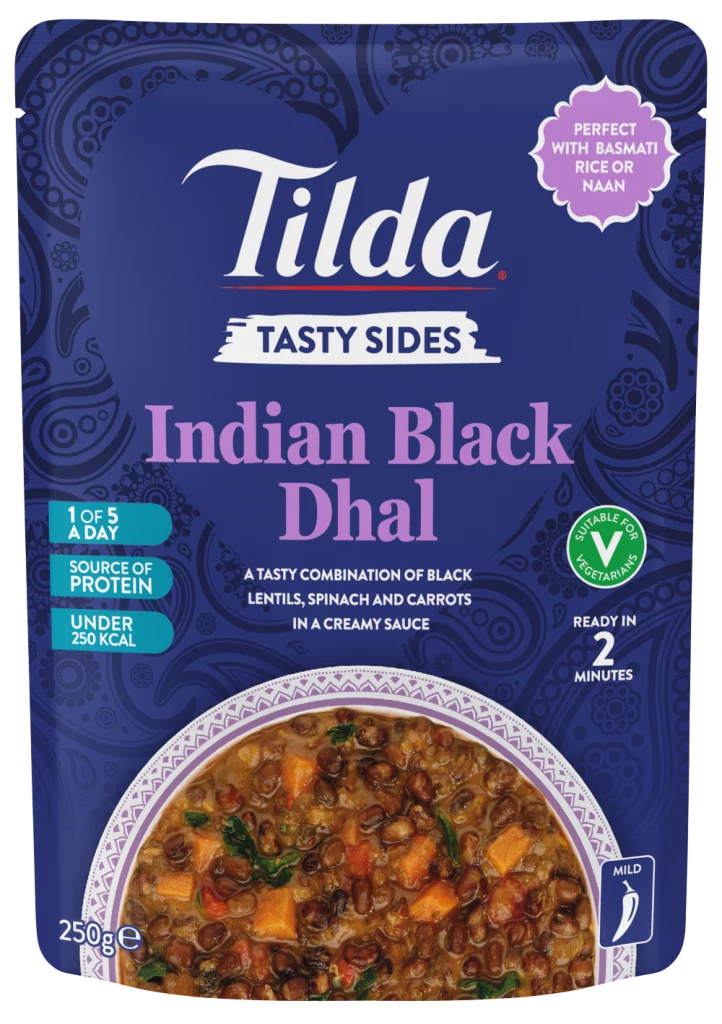

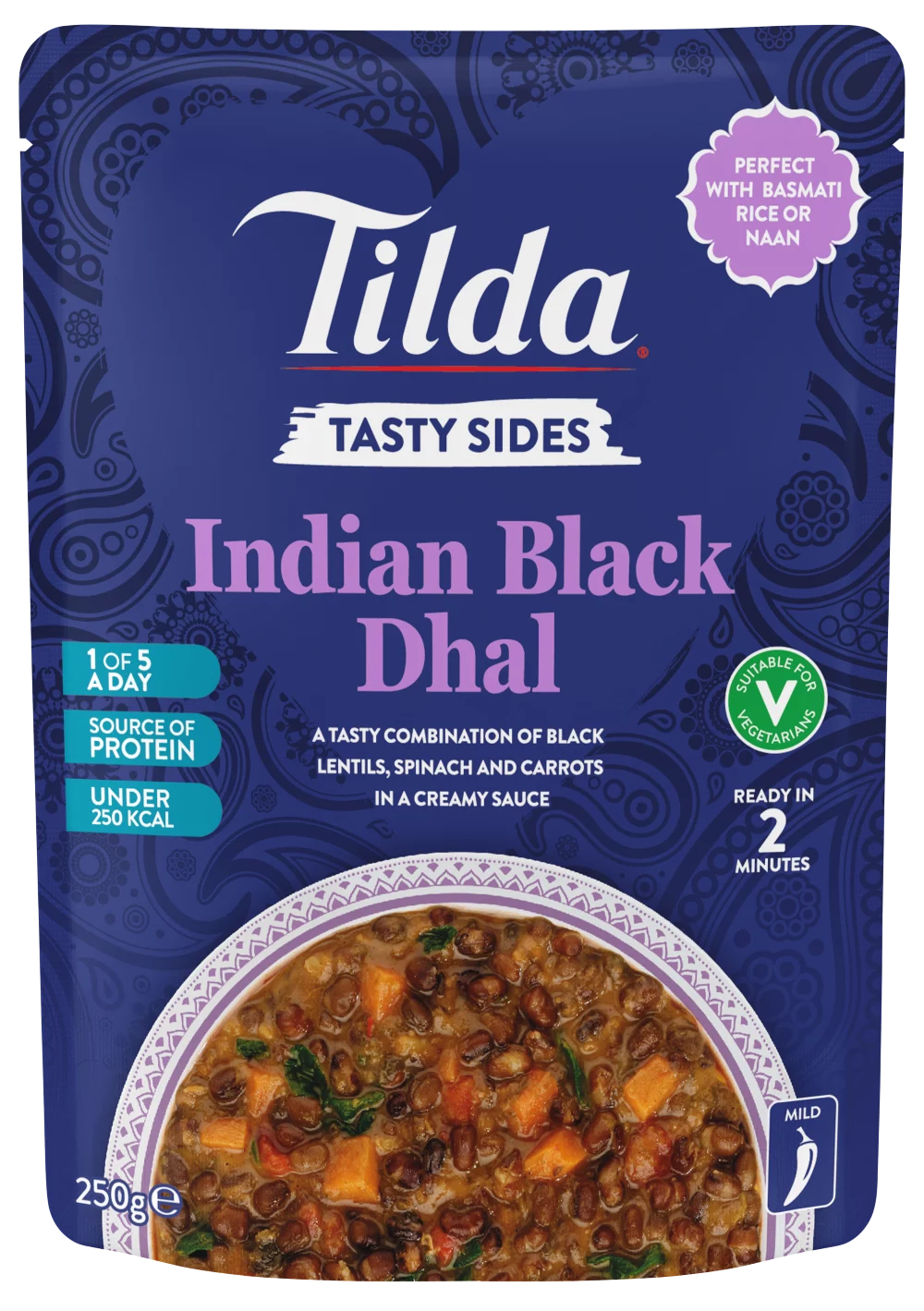

Tilda Products

Elevate mealtime with Tilda! Whether you’re cooking from scratch with our classic Dry Rice, enjoying the convenience of Microwave Rice, or savouring our new Meals & Sides range, we make eating well effortless. Even little ones can enjoy balanced, tasty bites with our Kids Rice. Made with quality ingredients and ready in minutes — delicious, every time!

Quick & Easy Recipes

Coconut Basmati Rice

Salmon and Coconut Buddha Bowl

Globally inspired, this nourishing recipe is loaded up with fresh ingredients and flavour, perfect at lunchtime! It also contributes to a varied and balanced diet.

Wholegrain Basmati and Quinoa Rice

Mixed Grain and Avocado Salad

Ready in less than 10 minutes, this tasty, quick and easy salad is the perfect addition to a BBQ on a warm, summer evening.

Lemon and Herbs Basmati Rice

Middle Eastern Falafel Pitta

Common street food in the Middle East, this tasty recipe is so easy to make! A simple dish bursting with flavours that will keep you going for the rest of the day. Feel free to add some chicken for a non-veggie option.

Purchase a pack of Tilda Boil in the Bag rice for a chance to win a £1,000 Lifestyle voucher and over 100 more prizes.

Enter now online* or instoreFrom the Blog

17 June 2022

15 Top Tips to Help Elevate your Lunch with Leftovers

Whether you’re running late for a school run or simply tired from running daily errands, lunch doesn’t need to be bland or boring.

11 July 2023

BBQ essentials and styles you need to know about

Supercharge your BBQ skills with these rubs, sauces and styles…

08 June 2022

Tips on How to Store and Reheat Cooked Rice

Everything you ever wanted to know about storing this kitchen staple.

Written by Alfred Bruin

28 June 2022

Feeding your little ones our Tilda Kids range

A delicious range of rice and vegetables.

About Us

Whether you are making a curry in a hurry or simple rice salad, we never compromise on purity, taste, quality or nutrition, so with Tilda you know you are in good hands. We often hear that our customers grew up eating Tilda and while we are well known for our Basmati rice, over our 50 year journey, we have become the experts in a wider variety of grains. We are always pushing ourselves to find the best possible way to deliver the best quality product to your table and be your guide through the world of rice and food.

Read About Us